A Composer Of Our Time

Merging

Past ~ Present ~ Future

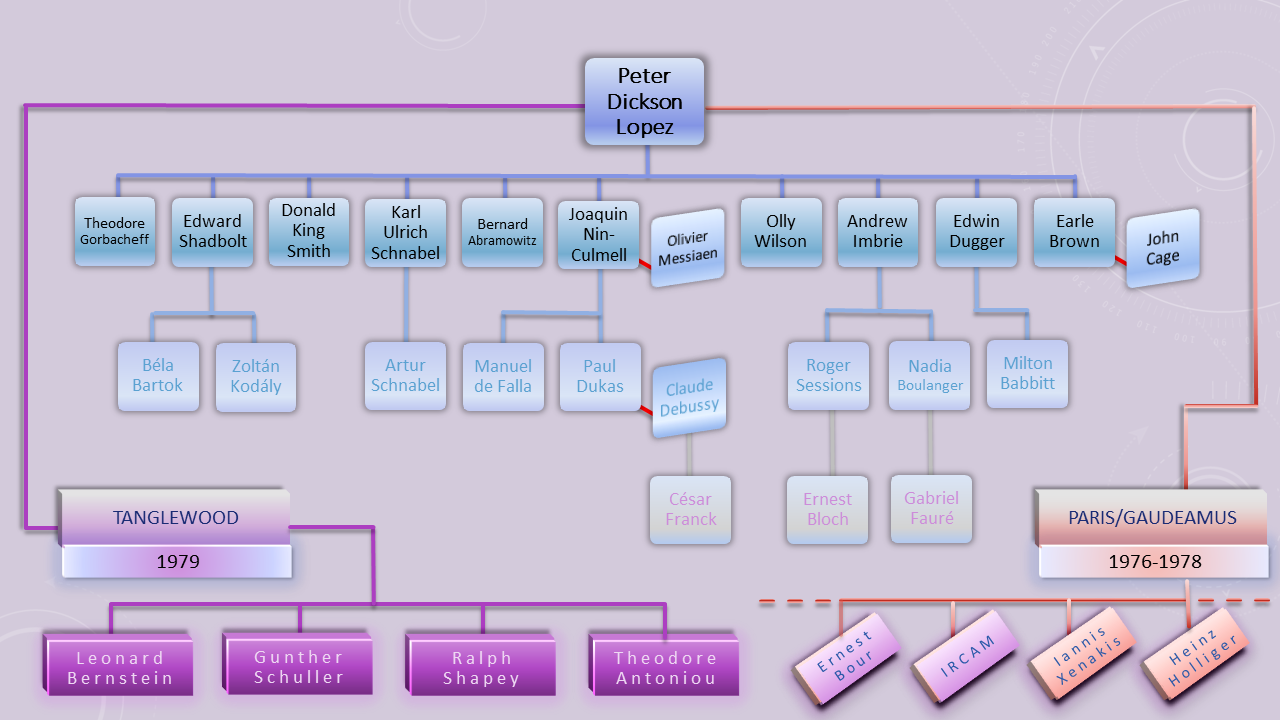

Composers throughout history have stood on the shoulders of their teachers, and certainly by our time, on the shoulders of the greats down through the ages. The chart of my music genealogy below illustrates all the people to whom I owe a great deal in my development. With some of these I have studied for many years, with others not quite so long or even for just a short time, and yet still with others perhaps just rubbing shoulders. All in all, whether these were my mentors or just leaving a deep and enduring impression on me in concert, lecture, or other events, all have contributed to who I am today as a composer. Even as I now stand on the shoulders of my own teachers supported by their words of wisdom, encouragement and example, so they themselves have stood on their own teachers, which is what the genealogy also illustrates. Red lines indicate key associations at that historical level but not direct connections to my own lineage. Immersive experiences during my two-year sojourn in Paris and at the festivals of Gaudeamus and Tanglewood in the late ‘70s, all made possible through my studies as a graduate student at the Berkeley campus of the University of California, served to wrap me in a kind of artistic bubble on steroids and which continue to energize and motivate me to this day.

I met Ernest Bour only once during the Gaudeamus Festival in the summer of 1979. At the time, I was too young, naïve, and inexperienced to appreciate the gravity and honor of being in the presence of such a luminary. I wasn’t aware that it was Bour’s recording of Ligeti’s Atmospheres that was used on the soundtrack to 2001: A Space Odyssey. I also did not know that he had conducted the European premiere of Berio’s Sinfonia in 1969. Indeed, he conducted world premieres of works by numerous legendary 20th century composers including Ligeti, Stravinsky and Xenakis.

In 1976, Maestro Bour was appointed as the permanent guest conductor of the Netherlands Radio Chamber Orchestra in Hilversum. Coincidentally, I took up residence in Paris in 1976 as a recipient of the George Ladd Prix de Paris. During my Paris sojourn, I wrote The Ship of Death which I subsequently submitted to the Gaudeamus Foundation competition for composers. This work was accepted for the 1979 Gaudeamus Festival, and so it was in Hilversum that I met Maestro Bour and collaborated with him on the world premiere performance and recording of The Ship of Death.

One day while we were driving together to a Festival destination, he shared something with me about his take on The Ship of Death which has stayed with me to this day. He expressed to me in his own way that he sensed in my music a breadth and expansive vision that was not unlike Mahler! I was so taken aback that I don’t think I said very much. Not knowing who Maestro Bour was at the time, I just took it later as a comforting compliment in light of the fact that my music did not win any award or recognition at the Festival, and that previously in Paris The Ship of Death had been rejected for performance consideration by the Ensemble Inter Contemporain (NB Ensemble Inter Contemporain was the then newly formed premier performing ensemble of IRCAM then headed by Pierre Boulez). But as I look back on it now, his encouraging words have, and continue to, buoy me up to survive the many disappointments, insults, negative reviews and comments, and broken promises that one experiences along the way. To be sure, any comparison of my work to Mahler is pure hyperbole, but Maestro Bour was precisely right about one thing: my music does strive to paint and explore an expansive environment!

While at Tanglewood during the summer of 1979 as a Fellowship Composer, I had the honor and privilege to audit one of Bernstein’s conducting classes. As good as the “student” conductors were, when Bernstein took the baton, the results were nothing but magical. It was amazing to hear how the performers responded to the slightest nuance of the Maestro to produce just the desired musical gesture, shape, or expression. But what was even more important to me at the time, and which has stayed with me over the years, is the Maestro’s preeminent focus on musical expression and clarity of its execution, which in a single word must be the most powerful and moving force engendered upon hearing great music. Alas, all too often in settings where one studies music composition, this aspect of composition is all but forgotten, ignored, or even eschewed as though the word expression itself is a profane word. To be sure, performers can not put expression into their performance if the composer didn’t put it there first! This view of music as preeminently an expressive medium does not enjoy unanimity of opinion among composers at large. Indeed, I recall Iannis Xenakis writing or saying something to the effect that the time for musical music is over. Ironically, when I listen to Xenakis’ music, I do come away with the feeling that I had experienced a very strong and powerful expressive voice. It just isn’t the musically musical voice of a bygone era.

Bernstein was to have met with the Fellowship composers that summer, and indeed this was something that I was really looking forward to. Much to my disappointment, Bernstein couldn’t make it. Though I am sure scheduling was a factor, I can’t help but think that his absence among us composers was in no small part due to the presence of the visiting guest composer that summer, Ralph Shapey, who was not exactly a fan of Bernstein. Aside from auditing the conducting master class, my other claim to fame in rubbing shoulders with Bernstein is that his daughter was the one to drive me to the airport when I left Tanglewood!